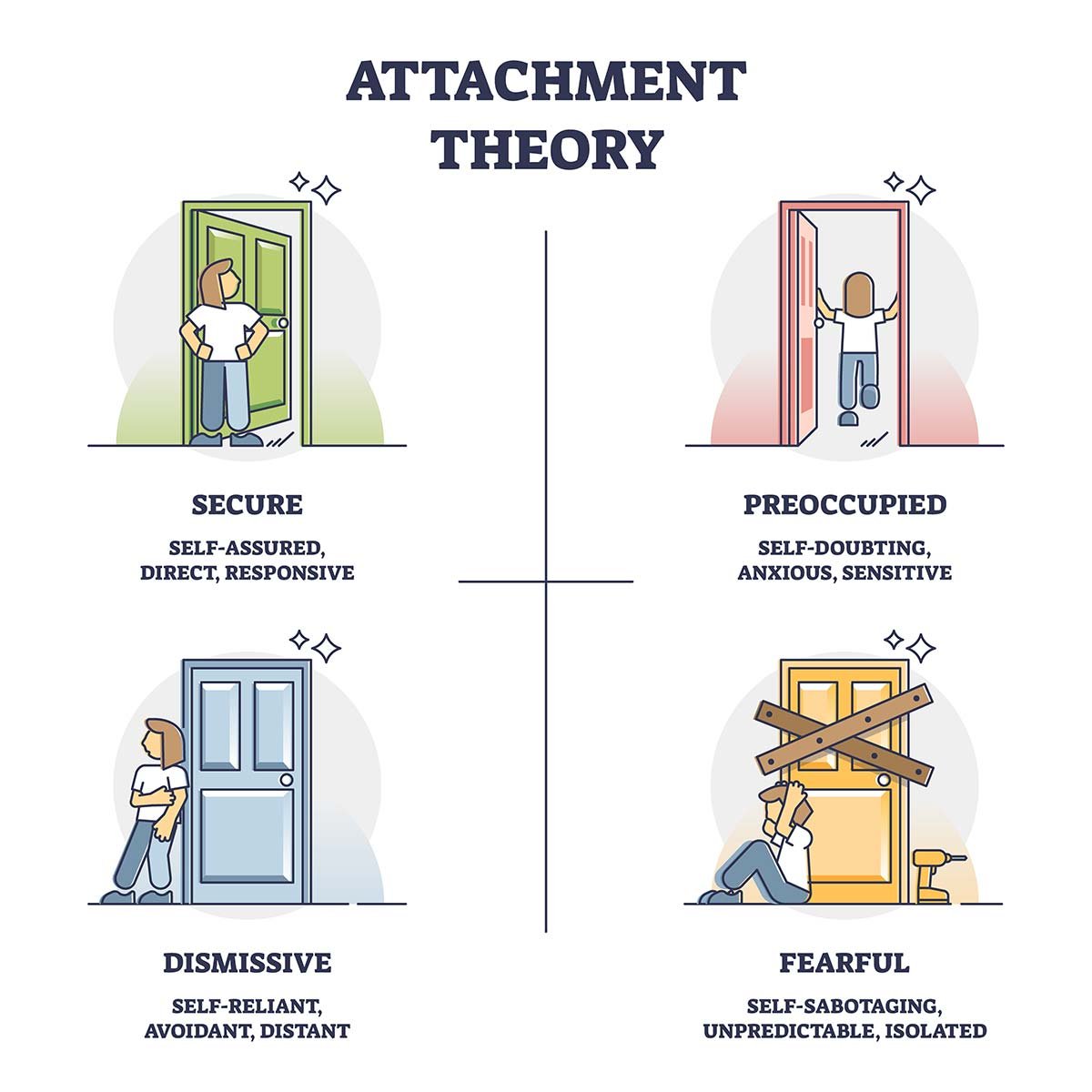

An attachment style describes how people relate to others based on how secure they feel. Secure attachment is characterized by feelings of trust and safety in relationships.

Secure attachment refers to a bond where individuals feel safe, supported, and connected, enabling them to express emotions freely, seek comfort from their partner, and confidently explore their environment knowing they have a reliable base to return to.

Key Takeaways

- An individual with a secure attachment style exhibits a consistent, interdependent, and confident style of relating in a relationship.

- Children who are securely attached feel safe and supported by their caregivers. Securely attached adults are capable of forming lasting relationships.

- The attachment style you develop in early childhood is thought to have a lifelong influence on your ability to communicate your emotions and needs, how you respond to conflict, and how you form expectations about your relationships.

- Although the attachment style you were raised with does not explain everything about your relationships and who you become as an adult, understanding your style may help explain patterns you notice in relationships.

- Secure attachment is essential for fostering healthy childhood development and adult relationships.

- Securely attached individuals maintain a healthy balance of relying on their partner and meeting their own needs. Due to this balance, they can create deeper intimacy through vulnerability while maintaining their individuality.

- Secure attachments with caregivers are believed to be essential for healthy development. It is considered that about 50% of the population has a secure attachment style, while the rest fall into one of the insecure categories (anxious, avoidant, and disorganized).

Signs in children

Infants with a secure attachment hold an internal model of the world as a safe place and a model of others as being kind and reliable.

Children with a secure attachment, having been regulated by their caregiver in times of stress,

develop skills to self-regulate their social, emotional, and cognitive behaviors.

In addition, securely attached children show balanced behavioral strategies, expressing their need for both intimacy and autonomy. Autonomy is particularly significant as it facilitates interaction with the environment.

Early signs can depict if a child is developing into a securely attached adult. These signs include:

- Positive response to the return of parents

- Comfortably interacts with others

- Comfortably explores and plays in new areas

- Prefers parents over strangers

- Seeks comfort from parents

Securely attached children use the caregiver as a secure base with

which to explore their social world and a safe haven to turn to during times of distress.

For a child to develop a secure attachment, they need to be raised in an environment where they feel protected and seen by their caregivers.

If a caregiver is not responsive to a child’s needs, the child may not be able to form a secure and stable bond.

How to raise a securely attached child

If a child is brought up in a nurturing and supportive environment where caregivers are responsive to the child’s needs, a secure bond is formed.

However, if a child perceives that their needs are not met, the child is not able to build a secure and stable bond with their caregivers.

1. Be a secure base physically and emotionally

Attachment figures can be seen as a ‘secure base’ that infants use to explore their social world. The more assured the infant is in the availability of their attachment figure in times of stress, the more likely they will interact with others and their environment.

Caregivers who provide a secure base allow infants to become autonomous, inquisitive, and experimental. When around their caregiver, the child should feel assured that no harm will come to them. They should know they will be fed, kept warm, and protected.

The caregiver is the child’s barrier against harm, so letting them know they are protected and loved is important in making them feel safe.

The child should be allowed the chance to develop freedom while still getting reassurance from their caregiver that they are nearby if they need to check in with them.

2. Ensure they feel seen and understood

A child’s signal for attention, such as crying, is their way of letting the caregiver know they require a need to be met. It is important that the caregiver reads these signals accurately and responds consistently.

If a caregiver is consistently responsive to the child’s needs appropriately, this lets the child know that when they need something, they can signal for it.

If the caregiver responds correctly, most of the time, the child should understand that their world is reliable and they can have some control over it.

Interactional synchrony focuses on coordinating nonverbal behaviors during social interactions, while emotional attunement is about the empathetic understanding and response to another person’s emotions.

2.1. Interactional Synchrony

Interactional synchrony is a form of rhythmic interaction between infant and caregiver involving mutual focus, reciprocity, and mirroring of emotion or behavior. Infants coordinate their actions with caregivers in a kind of conversation.

From birth, babies move in a rhythm when interacting with an adult, almost as if they were taking turns. The infant and caregiver are able to anticipate how each other will behave and can elicit a particular response from the other.

Interactional synchrony is most likely to develop if the caregiver attends fully to the baby’s state, provides playful stimulation when the infant is alert and attentive, and avoids pushing things when an overexcited or tired infant is fussy and sending the message “Cool it. I just need a break from all this excitement”.

Interactional synchrony can facilitate emotional attunement, as coordinated nonverbal behaviors may help individuals better understand and connect with each other’s emotional states.

2.2. Emotional Attunement

Attunement is a subtle process in which the parent is “tuned in” to the child’s emotional needs.

A mom (or caregiver) needs to be good at noticing the tiny and quick changes in a baby’s emotions. She (or he) then has to show the baby through their facial expressions, voice tone, and body language that they understand those emotions and share the experience with the baby.

When things go smoothly, attunement helps a child feel truly understood, accepted, and supported by their mom or caregiver.

This experiment is still considered an important finding in the study of how babies develop.

But, no one can be perfect all the time, so sometimes there will be misunderstandings or mistakes (called “mis-attunement” or “relationship ruptures”).

These bumps in the road are normal, and they can even be good for the relationship between the child and caregiver if the caregiver is able to fix the problem the right way.

In fact, it’s believed that for a strong bond to develop, caregivers only need to get it right about one-third of the time, which is comforting to know!

Attuned responses

According to Daniel Stem (2018, p. 139.), professor of Psychiatry at Cornell University Medical Center, sensitive (‘attuned’) responses from a caregiver follow three steps:

- “First, the parent must be able to read the infant’s feeling state from the infant’s overt behavior.

- Second, the parent must perform some behavior that is not a strict imitation but nonetheless corresponds in some way to the infant’s overt behavior.

- Third, the infant must be able to read this corresponding parental response as having to do with the infant’s original feeling experience and not just imitating the infant’s behaviour”.

2.3. Mis-attunement

Many parent-child relationships have strong love but lack emotional attunement. In these non-attuned relationships, children may feel loved but not genuinely understood or appreciated for their true selves.

They often repress emotions or aspects of themselves that they perceive as unacceptable to their parents.

Research by Lynne Murray (1985) has demonstrated that even warm responses to infants are not regulating unless they are exactly timed with their cues.

In 1975, Edward Tronick and his team introduced the “Still Face Experiment” at a child development research conference.

They showed that when a baby interacts with their mom who’s not responding and has no facial expression for three minutes, the baby quickly becomes sad and cautious.

When the mother “fails to respond appropriately,” the infant rapidly sobers and grows wary. He makes repeated attempts to get the interaction into its usual reciprocal pattern. When these attempts fail, the infant withdraws [and] orients his face and body away from his mother with a withdrawn, hopeless facial expression (p.452).

Proximate separation

A child’s perception of being emotionally understood and connected with others is crucial. However, certain stressful circumstances can cause caregivers to be emotionally distant, even if physically present. This condition of being physically close but emotionally separated is called “proximate separation.”

Proximate separation can be as distressing to a child as physical separation. Examples include a parent breaking intense eye contact with a child or overstimulating a resting child. These interactions register on an unconscious physiological level, even if the child isn’t consciously aware of the emotional disconnection. Such experiences shape a child’s future personality and emotional development.

Research by Allan Schore (2001, 2008) suggests that these types of emotional disconnections can cause physiological stress levels in a child that are comparable to physical separations.

These early experiences of proximate separation can influence adult relationships, leading individuals to seek out partners who replicate these non-attuned dynamics, continuing a cycle of emotional misattunement into adulthood.

3. Be comforting

The child should know that if they seek comfort, they will receive it from their caregivers.

If the caregivers are there to help soothe the child’s distress, they learn to see this as normal. When they grow up, they can use their caregiver’s actions as the template for managing their distress.

4. Ensure they feel valued

Caregivers can value their children by expressing happiness and pride over who they are. Healthy self-esteem can develop as a baby, which translates into later life.

Displaying pride in a child early in life can make them realize that they are unconditionally valued for what they achieve.

5. Support the child to explore their world

A child should be supported to explore their world in a way that makes them feel secure. Caregivers should aim to reassure the child that they believe in their abilities but stay close by if something goes wrong.

Try not to be overbearing or constantly tell them what they should be doing. Instead, give gentle guidance if they get stuck and allow them to grow while watching from a safe distance.

In this way, the child should develop a sense of freedom to explore their world and increase their confidence in their own skills.

Limiting a child from exploration, being overprotective, or keeping them boxed in may lead to the development of an anxious attachment pattern. Children need to learn to explore independently and feel safe doing so.

The independence and individuality that comes from childhood exploration contribute to a secure attachment style into adulthood.

Signs in adults

John Bowlby argued that one’s sense of security as a child is critical to their attachment style as an adult.

Adult relationships are likely to reflect early attachment style because the experience a person has with their caregiver in childhood would lead to the expectation of the same experiences in later relationships.

How To Know If Someone Has A Secure Attachment Style

Securely attached adults hold both a positive working model of self and others and therefore are comfortable with both intimacy and autonomy.

Such individuals typically display openness regarding expressing emotions and thoughts with others and are comfortable with depending on others for help while also being comfortable with others depending on them (Cassidy, 1994).

Notably, many secure adults may, in fact, experience negative attachment-related events, yet they can objectively assess people and events and assign a positive value to relationships in general.

A secure partner has complete confidence that their partner is there for them. They can balance the act of giving and receiving in a relationship.

Because they are securely attached, they experience less relationship anxiety, fear, or doubt and can focus on being present for their partner. They are interdependent and maintain a positive view of their partner.

Signs you are dating a person with a secure attachment

- They maintain a direct line of communication (you know where you stand with this person).

- They’re upfront about what they’re looking for in a partner and in a relationship.

- Comfortable with being vulnerable by sharing their emotions, experiences, fears, etc.

- Warm and empathetic.

- They make you feel safe and secure just by being around them.

- They’re able to be interdependent, meaning they’re ok on their own AND with others.

- Confident in expressing their affection.

- You feel you are able to get close to them emotionally AND physically.

- They talk of ex-partners with respect.

- They seem to view the world as a generally safe place and are able to trust others easily.

- Want their partner to have their own interests outside of the relationship.

- Respect their partner’s needs and boundaries (and also set their own).

Secure attachment sounds like…

“I’m sorry I reacted like that but I felt attacked. Can we talk about what happened? I want to make it right”

“I’m sorry I hurt you. I wasn’t right. I want us both to be happy & I acknowledge that it will take work.”

“I thought about what you said & want you to know that I hear you. I will try to help you meet your needs.”

“I know this is important but I don’t have the capacity to discuss it right now.”

Is it too late to form a secure attachment?

There appears to be a continuity between early attachment styles and the quality of later adult romantic relationships. This idea is based on the internal working model, where an infant’s primary attachment forms a model (template) for future relationships.

Attachment security, or the stability and trust one feels in interpersonal relationships, can be developed within a consistent and dependable relationship, but it’s generally believed that building this kind of security takes a significant amount of time.

During adulthood, new attachment bonds are formed, which may become a significant source of support during periods of distress, goal achievement, and exploration.

Romantic partners function as attachment figures and can become a source of comfort and felt security for the other member of the relationship.

Romantic relationships are likely to reflect early attachment style because the experience a person has with their caregiver in childhood would lead to the expectation of the same experiences in later relationships, such as friends and romantic partners.

However, other researchers have proposed that rather than a single internal working model, which is generalized across relationships, each type of relationship comprises a different working model.

This means a person could be insecurely attached to their parents but securely to a romantic partner or friend.

For example, the highest level internal working model comprises beliefs and expectations across all types of relationships, and lower level models hold general rules about specific relations, such as romantic or parental, underpinned by models specific to events within a relationship with a single person (Collins & Read, 1994; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985).

Navigating Relationships with Insecure Attachment: Steps for Personal Growth and Building Secure Bonds:

If you identify with having an insecure attachment style, it’s essential to recognize that you have the power to evolve and cultivate healthier relationships.

If you find yourself with an insecure attachment style, building close relationships with securely attached friends and romantic partners can play a pivotal role in your personal growth and emotional wellbeing. Securely attached individuals can offer:

-

Seek a Secure Base: Just as you need stability during childhood, it’s crucial to find or create emotionally stable environments as an adult.

This might mean surrounding yourself with reliable friends or seeking partners who provide consistent love and care. Prioritize relationships where you feel safe and valued.

-

Prioritize Feeling Seen and Understood: Foster open communication in your relationships. Express your needs and feelings and encourage your partner or friends to do the same. Mutual understanding is the foundation of a deep and fulfilling connection.

-

Foster Interactional Synchrony and Emotional Attunement:

- Interactional Synchrony: Secure individuals typically excel at active engagement in conversations. They share experiences and emotions and are genuinely present in the moment.

Engaging with such individuals can not only enrich your interactions but also strengthen your bond, allowing you to experience a fulfilling connection.

- Emotional Attunement: Secure friends and partners often possess a keen ability to connect with their own emotions and the emotions of others.

When in the company of securely attached individuals, you’ll find it easier to recognize and reflect upon emotional shifts within yourself.

They can also guide you in understanding and resonating with the feelings of those around you, fostering a deeper emotional bond.

- Interactional Synchrony: Secure individuals typically excel at active engagement in conversations. They share experiences and emotions and are genuinely present in the moment.

Learn More

Can a secure person become anxious?

Yes, a secure person can become anxious due to traumatic experiences. For example, a secure person may encounter a relationship with a partner who gets very close and then withdraws or stonewalls their partner inconsistently. This type of unpredictability can be painful and lead to the secure person becoming anxious.

What are the main contributors to developing a secure attachment?

The major factors which lead to a secure attachment style are being raised by a caregiver who offers a safe base, room for exploration, and consistency. Secure attachment is maintained by fully healing and processing relationships before moving on to another person.

In conclusion, a secure attachment style is a healthy and balanced way of relating with oneself and others. They come naturally due to childhood conditioning or can be learned with psychological healing.

What is the influence of secure attachment on childhood friendships?

According to attachment theory, a child with a secure attachment style should be more confident in interactions with friends.

Considerable evidence has supported this view. For example, the Minnesota study (2005) followed participants from infancy to late adolescence and found continuity between early attachment and later emotional/social behavior.

Securely attached children were rated most highly for social competence later in childhood and were less isolated and more popular than insecurely attached children.

Hartup et al. (1993) argue that children with a secure attachment type are more popular at nursery and engage more in social interactions with other children. In contrast, insecurely attached children tend to rely more on teachers for interaction and emotional support.

Further Information

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1994). Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychological inquiry, 5(1), 1-22.

- McCarthy, G. (1999). Attachment style and adult love relationships and friendships: A study of a group of women at risk of experiencing relationship difficulties. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 72(3), 305-321.

- Greater Good Magazine of Berkeley University of California. How to stop attachment insecurity from ruining your love life.

- BPS Article- Overrated: The predictive power of attachment

- How Attachment Style Changes Through Multiple Decades Of Life

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Baldwin, M.W., & Fehr, B. (1995). On the instability of attachment style ratings. Personal Relationships, 2, 247-261.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L.M. (1991). Attachment Styles Among Young Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 (2), 226–244.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume I. Attachment . London: Hogarth Press.

Brazelton, T. B., Tronick, E., Adamson, L., Als, H., & Wise, S. (1975). Early mother-infant reciprocity. Parent-infant interaction, 33(137-154), 122.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (p. 46–76). The Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1995). Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 267–283.

Bylsma, W. H., Cozzarelli, C., & Sumer, N. (1997). Relation between adult attachment styles and global self-esteem. Basic and applied social psychology, 19 (1), 1-16.

Conrad, R., Forstner, A. J., Chung, M. L., Mücke, M., Geiser, F., Schumacher, J., & Carnehl, F. (2021). Significance of anger suppression and preoccupied attachment in social anxiety disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC psychiatry, 21 (1), 1-9.

Caron, A., Lafontaine, M., Bureau, J., Levesque, C., and Johnson, S.M. (2012). Comparisons of Close Relationships: An Evaluation of Relationship Quality and Patterns of Attachment to Parents, Friends, and Romantic Partners in Young Adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44 (4), 245-256.

Cassidy, J., & Berlin, L. J. (1994). The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child development, 65 (4), 971-991.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations of adult attachment: The structure and function of working models. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.) Advances in personal relationships, Vol. 5: Attachment processes in adulthood(pp. 53-90). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Favez, N., & Tissot, H. (2019). Fearful-avoidant attachment: a specific impact on sexuality?. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(6), 510-523.

Field, T. (1985). Attachment as psychobiological attunement: Being on the same wavelength. The psychobiology of attachment and separation, 4152, 454.

Finzi, R., Cohen, O., Sapir, Y., & Weizman, A. (2000). Attachment styles in maltreated children: A comparative study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 31 (2), 113-128.

Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: Four lessons. Current opinion in psychology, 25, 26-30.

Haft, W. L., & Slade, A. (1989). Affect attunement and maternal attachment: A pilot study. Infant mental health journal, 10(3), 157-172.

Hashworth, T., Reis, S., & Grenyer, B. F. (2021). Personal agency in borderline personality disorder: The impact of adult attachment style. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2224.

Hartup, W. W. (1993). Adolescents and their friends. New directions for child and adolescent development, 1993 (60), 3-22.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511–524.

Hoghughi, M., & Speight, A. N. P. (1998). Good enough parenting for all children—a strategy for a healthier society. Archives of disease in childhood, 78(4), 293-296.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2), 66-104.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy . Ablex Publishing.

Meins, E. (2013). Sensitive attunement to infants’ internal states: Operationalizing the construct of mind-mindedness. Attachment & Human Development, 15(5-6), 524-544.

Moghadam, M., Rezaei, F., Ghaderi, E., & Rostamian, N. (2016). Relationship between attachment styles and happiness in medical students. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 5 (3), 593–599.

Murray, L. (1985). Emotional regulations of interactions between two-month-oldsand their mothers. Social perception in infants, 177-197.

Powell, B., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Marvin, B. (2013). The circle of security intervention: Enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationships. Guilford publications.

Schore, A. N. (2001). Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant mental health journal: official publication of the world association for infant mental health, 22(1‐2), 7-66.

Schore, J. R., & Schore, A. N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical social work journal, 36(1), 9-20.

Sechi, C., Vismara, L., Brennstuhl, M. J., Tarquinio, C., & Lucarelli, L. (2020). Adult attachment styles, self-esteem, and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Health Psychology Open, 7 (2), 2055102920947921.

Simpson, J. A. (1990). Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 59 (5), 971.

Stern, D. N. (2018). The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental Psychology. Routledge.

Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71 (3), 684-689.

Weinberg, M. K., Beeghly, M., Olson, K. L., & Tronick, E. (2008). A still-face paradigm for young children: 2½ year-olds’ reactions to maternal unavailability during the still-face. The journal of developmental processes, 3(1), 4.