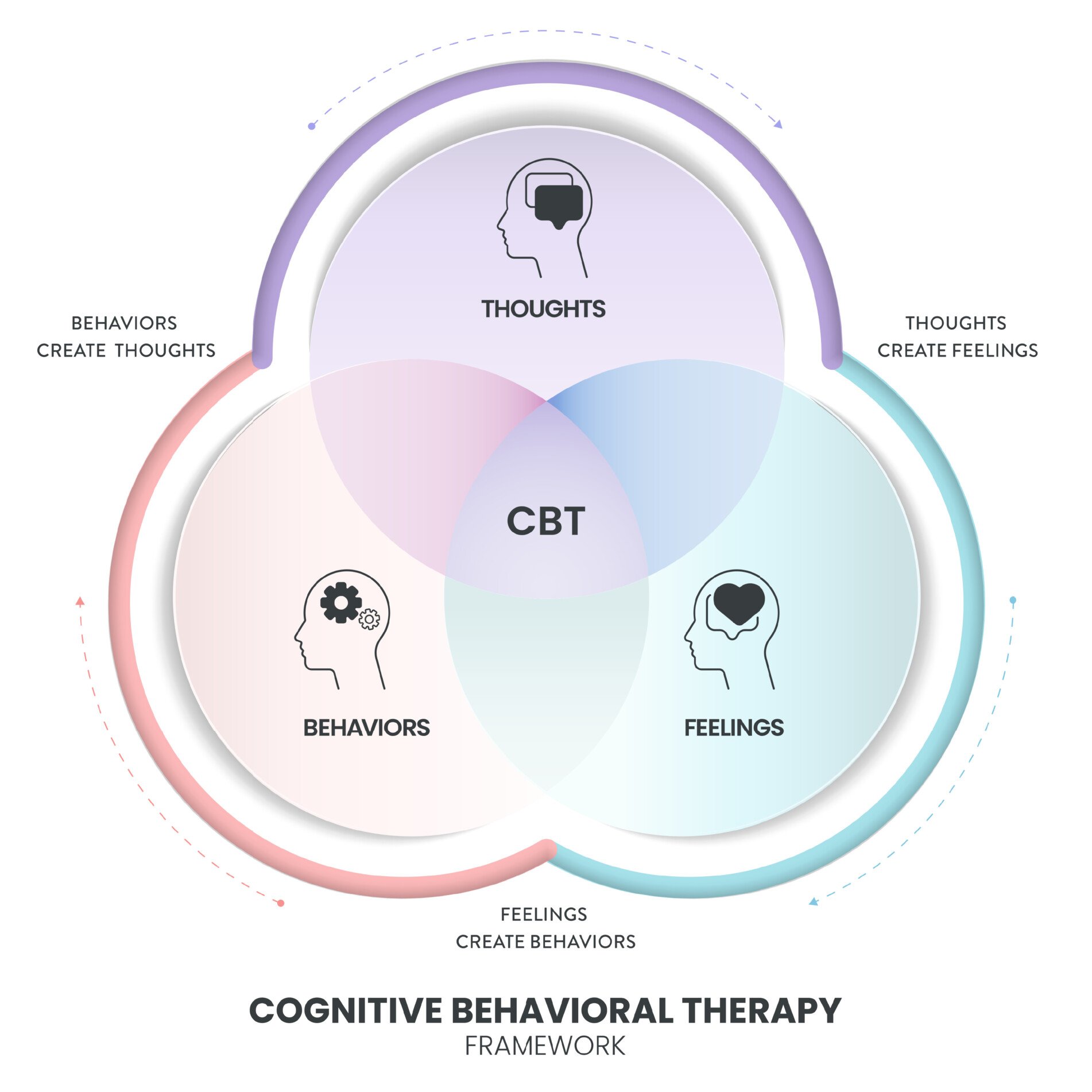

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps with social anxiety by challenging negative thoughts about social situations and gradually exposing individuals to feared scenarios. It aims to reduce anxiety by changing thought patterns and behaviors.

Mindfulness, in contrast, promotes present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance of thoughts and feelings. It can decrease self-focused attention and improve emotional regulation.

Combining these approaches may offer a comprehensive strategy for managing social anxiety, addressing both cognitive distortions and attentional processes.

Noda, S., Shirotsuki, K., & Nakao, M. (2024). Low-intensity mindfulness and cognitive–behavioral therapy for social anxiety: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), Article 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05651-0

Key Points

- The primary methods of this study included a 4-session mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (M-CBT) program for individuals with high social anxiety symptoms.

- Factors like negative cognition generated when paying attention to others in probability bias, fear of negative evaluation by others, dispositional mindfulness, depressive symptoms, and subjective happiness were significantly improved by the M-CBT intervention.

- The research, while enlightening, has certain limitations, such as a small sample size, lack of comparison to traditional CBT, and potential cultural specificity to Japanese university students.

- This study introduces the potential of combining mindfulness training with cognitive restructuring techniques to address social anxiety symptoms and cognitive biases.

Rationale

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterized by intense fear or anxiety in social situations where an individual may feel scrutinized by others (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is currently the most effective treatment for SAD symptoms (Mayo-Wilson et al., 2014).

However, some patients do not experience significant improvement even after completing CBT treatment (Rodebaugh et al., 2004). The remission rate for SAD through CBT is approximately 40% (Loerinc et al., 2015; Springer et al., 2018; Ginsburg et al., 2011).

Moscovitch et al. (2012) found that non-responders to CBT did not show significant decreases in cost and probability biases, which are maintaining factors in SAD.

Mindfulness training (MT) has shown promise in reducing cost/probability bias and social anxiety symptoms (Noda et al., 2022; Schmertz et al., 2012).

Combining MT with cognitive restructuring techniques may enhance the efficacy of treatment for SAD, particularly for those who do not respond to traditional CBT.

This study aims to examine the effectiveness of a 4-session mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy (M-CBT) program for individuals with high social anxiety symptoms.

The program was designed as a brief, low-intensity treatment module specifically targeting those with high levels of cost/probability bias and social anxiety symptoms.

Method

The study employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design with two groups: an intervention group that underwent M-CBT and a control group that did not receive any treatment.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. The intervention group underwent a 4-session M-CBT program, with each session lasting 90 minutes and delivered once a week in a group format.

The control group did not participate in any intervention. Questionnaires were administered to both groups before and immediately after the intervention period and one month later as a follow-up.

Sample

The study included 50 Japanese undergraduate students (37 women and 13 men) with high social anxiety symptoms.

Participants were required to score 44 or higher on the Japanese version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) and 69 or lower on the Japanese version of the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS).

Measures:

- Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS): Measures social anxiety and avoidance behavior in 24 social situations. It assesses both the fear experienced and the degree of avoidance in these situations.

- Speech Cost/Probability Scale (SCPS): Assesses cost and probability bias in speech situations. It evaluates the perceived negative consequences (cost) and likelihood (probability) of negative outcomes in social speaking scenarios.

- Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (FNE): Measures fear of negative evaluation by others. It assesses the degree to which individuals experience apprehension about others’ evaluations and distress over negative evaluations.

- Self-Focused Attention Scale (SFA): Measures self-focused attention, which is the tendency to focus on internal thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations in social situations.

- Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): Assesses dispositional mindfulness across five dimensions: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience.

- Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS): Measures depressive symptoms, including psychological and physiological symptoms associated with depression.

- Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS): Assesses subjective happiness, measuring global subjective happiness through self-evaluation and comparison to peers.

Statistical measures

The study used analysis of covariances (ANCOVA) to test the effectiveness of M-CBT.

Simple effect analyses using Bonferroni’s method were performed for variables showing significant interactions.

Cohen’s d was calculated to examine effect sizes within the intervention group.

Results

Hypothesis 1: M-CBT will be effective in reducing social anxiety symptoms and cost/probability bias.

Results: Significant interactions were found in probability bias total score and probability bias in the negative cognition generated when paying attention to others. No significant interactions were observed in social anxiety symptoms (LSAS scores) or overall cost bias.

Hypothesis 2: M-CBT will improve fear of negative evaluation and self-focused attention.

Results: Significant interactions were found in fear of negative evaluation. No significant interactions were observed in self-focused attention.

Hypothesis 3: M-CBT will enhance dispositional mindfulness and improve depressive symptoms and subjective happiness.

Results: Significant interactions were found in dispositional mindfulness, depressive symptoms, and subjective happiness.

Insight

The study found that the 4-session M-CBT program was effective in improving several aspects related to social anxiety, particularly probability bias in negative cognition generated when paying attention to others, fear of negative evaluation, dispositional mindfulness, depressive symptoms, and subjective happiness.

However, the program did not show significant improvements in overall social anxiety symptoms or cost bias.

These findings suggest that combining mindfulness training with cognitive restructuring techniques may be beneficial for addressing specific cognitive biases and related symptoms in individuals with high social anxiety.

The study extends previous research by examining the potential of a brief, low-intensity intervention that incorporates both mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral approaches.

Future research could focus on comparing the efficacy of M-CBT to traditional CBT, examining the long-term effects of the intervention, and investigating the mechanisms through which mindfulness training enhances cognitive restructuring techniques.

Strengths

The study had several methodological strengths, including:

- Use of a randomized controlled trial design

- Inclusion of both immediate post-intervention and follow-up assessments

- Use of validated measures for assessing social anxiety and related constructs

- Implementation of a brief, low-intensity intervention that could be easily replicated and scaled

Limitations

This study also had some methodological limitations, including:

- The sample consisted only of Japanese university students, limiting generalizability to other populations and cultures.

- The study lacked a comparison group receiving traditional CBT, making it difficult to determine the unique contributions of combining mindfulness with cognitive restructuring.

- The sample size was relatively small, which may have limited statistical power.

- The follow-up period was only one month, preventing assessment of long-term effects.

- The study relied on self-report measures, which may be subject to bias.

These limitations impact the generalizability of the results and the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of M-CBT compared to other interventions.

Implications

The results of this study have several implications for clinical psychology practice and research:

- Brief, low-intensity interventions combining mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral techniques may be effective for addressing specific aspects of social anxiety, particularly cognitive biases.

- The improvement in dispositional mindfulness, depressive symptoms, and subjective happiness suggests that M-CBT may have broader benefits beyond social anxiety symptoms.

- The lack of significant improvement in overall social anxiety symptoms and cost bias indicates that longer or more intensive interventions may be necessary for some individuals.

- The differential effects on probability bias versus cost bias highlight the importance of targeting specific cognitive processes in social anxiety interventions.

- The study provides a foundation for further research into the mechanisms by which mindfulness training may enhance cognitive restructuring techniques in the treatment of social anxiety.

Variables that may influence the results include cultural factors, severity of social anxiety symptoms, and individual differences in responsiveness to mindfulness-based interventions.

References

Primary reference

Noda, S., Shirotsuki, K., & Nakao, M. (2024). Low-intensity mindfulness and cognitive–behavioral therapy for social anxiety: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), Article 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05651-0

Other references

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Ginsburg, G. S., Kendall, P. C., Sakolsky, D., Compton, S. N., Piacentini, J., Albano, A. M., Walkup, J. T., Sherrill, J., Coffey, K. A., Rynn, M. A., Keeton, C. P., McCracken, J. T., Bergman, L., Iyengar, S., Birmaher, B., & March, J. (2011). Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: Findings from the CAMS. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(6), 806–813. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025933

Loerinc, A. G., Meuret, A. E., Twohig, M. P., Rosenfield, D., Bluett, E. J., & Craske, M. G. (2015). Response rates for CBT for anxiety disorders: Need for standardized criteria. Clinical psychology review, 42, 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.004

Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D. M., Ades, A. E., & Pilling, S. (2014). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 368-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

Moscovitch, D. A., Gavric, D. L., Senn, J. M., Santesso, D. L., Miskovic, V., Schmidt, L. A., McCabe, R. E., & Antony, M. M. (2012). Changes in judgment biases and use of emotion regulation strategies during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: Distinguishing treatment responders from nonresponders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 261-271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9371-1

Noda, S., Shirotsuki, K., & Sasagawa, S. (2022). Self-focused attention, cost/probability bias, and avoidance behavior mediate the relationship between trait mindfulness and social anxiety: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 942801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.942801

Rodebaugh, T. L., Holaway, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2004). The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(7), 883-908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.007

Schmertz, S. K., Masuda, A., & Anderson, P. L. (2012). Cognitive processes mediate the relation between mindfulness and social anxiety within a clinical sample. Journal of clinical psychology, 68(3), 362-371. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20861

Springer, K. S., Levy, H. C., & Tolin, D. F. (2018). Remission in CBT for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 61, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.03.002

Keep Learning

- How might cultural factors influence the effectiveness of M-CBT for social anxiety symptoms?

- What potential mechanisms could explain the differential effects of M-CBT on probability bias versus cost bias?

- How could the M-CBT program be modified to potentially improve its effectiveness for overall social anxiety symptoms?

- What ethical considerations should be taken into account when developing and implementing brief, low-intensity interventions for mental health issues?

- How might the combination of mindfulness training and cognitive restructuring techniques be applied to other anxiety disorders or mental health conditions?