Key Takeaways

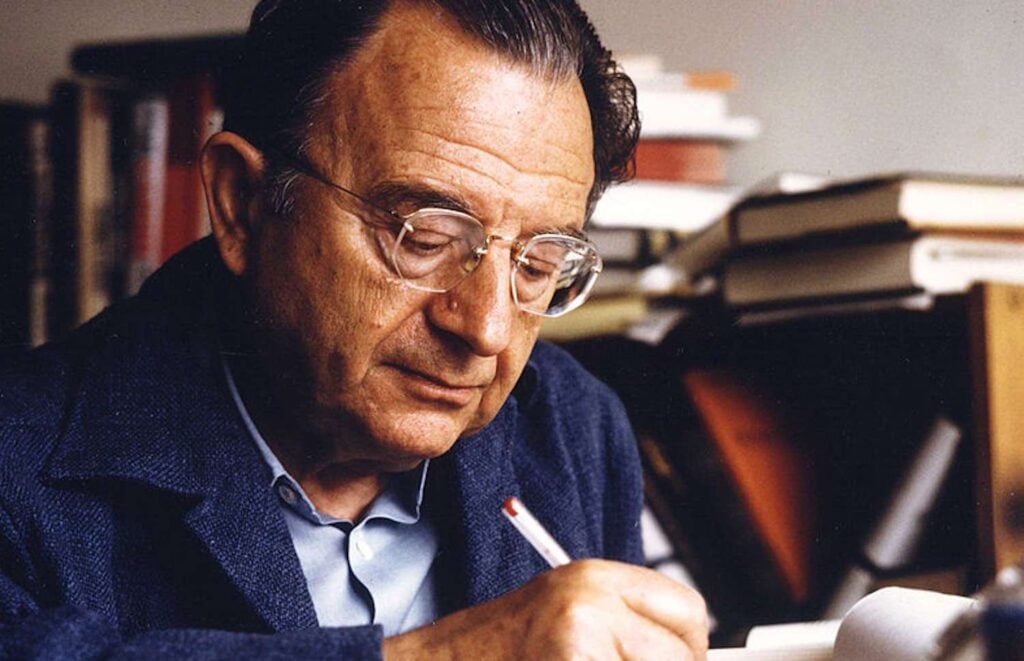

- Erich Fromm (1900-1980) was a German-American psychoanalyst associated with the Frankfurt School, who emphasized culture’s role in developing personality. He advocated psychoanalysis as a tool for curing cultural problems and thus reducing mental illness.

- Fromm believed that character in humans evolved as a way for people to meet their needs. Unlike Freud, he did not believe that character was fixed.

- Fromm outlined five essential human needs: relatedness, rootedness, transcendence, sense of identity, and frame of orientation. The absence of these, according to Fromm, would cause mental and social problems such as alienation.

- Fromm envisioned ideal versions of society and religion that emphasized freedom and meeting human needs. In doing so, he became one of the founders of humanistic socialism.

Life Overview

Erich Fromm was a German-born American psychoanalyst and social philosopher who emphasized the cultural determinants of personality.

His works investigated emotional problems in free societies and advocated psychoanalysis as a cure for cultural ills and as a tool to aid the development of a non-neurotic society.

Fromm, born in Frankfurt, was educated in Heidelberg and Munich before establishing a private psychotherapy practice in 1925. Fromm began as a disciple of Sigmund Freud, combining his psychological theories with Karl Marx’s social principles.

He used a unique method of psychoanalysis that involved confronting the patient both as his therapist and as another empathetic person, stressing that there is no trait or factor present in the patient that is not present in everyone else (Maccoby, 1980).

Fleeing Nazi Germany, Fromm moved to Chicago in 1933 to lecture at the Psychoanalytic Institute. He taught at several American universities and expanded his views to incorporate the principles of Zen Buddhism.

In 1957, he co-founded the National Committee for Sane Nuclear Policy. Fromm also wrote a number of books and articles for academics and the general public alike (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm first gained popularity with the general public with his book Escape From Freedom, which explained man’s unconscious fear of freedom and the appeal of authoritarian political systems.

This book largely shaped intellectual thought in America at the time and caused Fromm to be categorized as a neo-Freudian, together with Karen Horney and Harry Stack Sullivan.

Although these three figures differ, according to Fromm, they each share an emphasis on social and cultural factors and a critical attitude to Freud’s theory of the primacy of sexual instinct.

In 1951, Fromm became a professor at the National University of Mexico, where he founded the Mexican Institute of Psychoanalysts and regularly traveled to the United States before settling in Switzerland in 1971 (Maccoby, 1980).

Themes

Fromm developed several key themes, elaborating and refining his ideas progressively. One theme is social character, which relates the psychoanalytic theory of dynamic motivation to socio-economic factors.

The second theme is Fromm’s revision of Freud’s psychoanalysis, particularly his emphasis on aggression and destructiveness.

The third theme involves his critique of industrialized society, and his fourth is his analysis of religion and its relation to human development (Maccoby, 1980).

Social Character

Fromm built his theories of social character on Freud’s concept that character traits are dynamic. He believed that character structure explains actions, thoughts, and ideas: what motivates people and what they find satisfying or frustrating.

Fromm accepted Freud’s clinical description of character orientations in his psychosexual theory of character development. Two of these are the anal and the oral-receptive characters.

The anal, or anal-retentive personality is stingy, compulsively seeking order and tidiness. People who are anal-retentive are said to be fixated on the anal stage of development, which takes place between ages 18 months and three years.

Meanwhile, the oral-retentive personality describes people who are caught in the first psychosexual development stage, which happens from birth to eighteen months old.

Freud believed that people who are fixated on the oral stage of development have a sarcastic, sadistic personality and are prone to oral conditions such as smoking, overeating, and alcoholism.

Although Fromm accepted both of these concepts, he rejected libido theory as explaining character development (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm held that, although physiological needs must be satisfied, they are not the basic inner forces that determine a person’s actions, feelings, and thoughts.

Fromm believed that Character is the equivalent of an animal’s instinctive determinism, which humans had lost. It is a way that people can channel their energy and create structure through assimilation and socialization.

The development of Character, according to Fromm, allowed people to satisfy their needs for physical survival, the need to be emotionally related to others for defense, work, material possessions, sexual satisfaction, play, the upbringing of the young, and the transmission of knowledge (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm believed that social character is fundamental to character structure and is shared by most members of a cultural or social group. Rather than being a statistical measure or the traits shared by a majority, social character can be understood in terms of a socioeconomic structure — who owns the means to produce things.

Fromm contended that social character was intended to shape the energies of the members of a society in a way that behavior was not a matter of conscious decision whether or not to follow the social pattern but one of wanting to act as they have to act and, at the same time, finding gratification in acting according to the requirements of the culture.

This had the ultimate goal, Fromm believed, of allowing the society to function continuously.

One example of social character was Fromm’s (1951) revision of Freud’s concept of the anal character, which involves inner drives for orderliness, frugality, punctuality, and respect for authority. Fromm believed that this met the economic needs of the middle class in the nineteenth century.

However, in twentieth-century advanced capitalist societies, the social character is being replaced by another oriented toward consumption and fitting into bureaucratic structures through adaptation to their rules and regulations (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm used the social character to describe the social conflict as well as adaptation. As conditions change, a social character may no longer fit. The resentment and frustration that results transforms social cement into an explosive force.

Fromm also held that social needs can conflict with those stemming from the nature of people and their inherent need for love, solidarity with other humans, and the development of reason and creative talents.

Societies that do not satisfy these human needs will, according to Fromm, develop a “socially patterned defect (Maccoby, 1980).

Revision of Freudian Psychoanalysis and Psychopathology

Fromm had what has been considered to be a complex relationship with Freud and his work (Maccoby, 1980). Fromm criticized Freud’s theory and his tendency to demand ideological purity in psychoanalysis (1959).

However, Fromm also sought to develop and preserve what he considered to be the essential elements of Freud’s discoveries: making the unconscious conscious and the science of the irrational (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm (1970) criticized Freud’s model of man as being overly determined by his social views, such as the belief in patriarchy and the belief that people are fundamentally self-centered.

Fromm argued that in limiting his criticism of social norms to sexuality, Freud was handicapped in developing the full implication of his discoveries.

For example, Fromm argued that in his case study of “Little Hans,” Freud’s model of man caused him to misinterpret clinical evidence and underestimate the importance of the child’s relationship with his mother before the Oedipal stage.

Fromm also saw mature love as requiring equality between the sexes (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm rejected Freud’s instinct theories, instead seeing psychopathology as rooted in character. In his book Escape from Freedom, Fromm describes sadism and masochism as outcomes of a basic need for relatedness.

Fromm believed that humanity’s inability to endure feelings of powerlessness, uncertainty, and separateness led to psychopathology (Maccoby, 1980).

Fromm describes three main pathological forces of the psyche (1964). Two of these, incestuous fixation and narcism, are based on Freudian concepts, and the third, necrophilia, is Fromm’s own discovery (Maccoby, 1980).

Critique of Industrialized Society

Fromm notably built upon the early works of Karl Marx in his book, The Sane Society, and later published two books on Marxism.

The Sane Society was intended to be a continuation of his first work, Escape from Freedom, published 15 years earlier (Tillich, 1955), expanding between his prior psycho and socio-analysis to develop an image of a future society where the health of the whole supports the health of every individual.

In The Sane Society, Fromm describes the “alienation” of man in mid-twentieth century Democracy (Fromm, 1955). Fromm considered this alienation a necessity of human development and, thus, something which can be overcome in the course of human development. Fromm’s sane society conquers alienation (Tillich, 1955).

Simultaneously, Fromm sought to emphasize the ideal of freedom in a way missing from contemporary Soviet Marxism.

Ultimately, Fromm branded Western capitalism and Soviet communism as dehumanizing and causal in creating alienation. Ultimately, The Sane Society established Fromm as a founder of socialist humanism (Fromm, 2017).

Fromm’s Five Human Needs

Fromm postulated that there are five fundamental human needs: relatedness, rootness, transcendence, sense of identity, and frame of orientation (Das, 1993).

Relatedness

Fromm discussed the problem of alienation in contemporary society heavily. He believed that alienation was the problem that resulted when people’s need for relatedness was not met.

This need was so important to form that he considered alienation to be the “central problem of mental health.” (Fromm, 2017).

Fromm expanded on Marx’s idea that alienation was undesirable for people to talk about. He believed that alienation led to boredom, which Fromm regarded as an enormous psychological, and thus social, problem.

To Fromm, relatedness was the source of psychological energy, joy, well-being, and identity, and its loss dissipated this energy away.

To Fromm, it’s a lack of active relatedness to the world and our own feelings that result from social circumstances that prevent people from developing genuine, loving, productive relationships.

Rootedness and Unity

Fromm considered the need for rootedness and unity to be variations on the need for relatedness. He believed that people seek unity because of an existential split between the human and nonhuman world.

Fromm believed that this condition would be unbearable” if humans would not establish a sense of unity within themselves and with the natural and human world outside.

As with relatedness, Fromm believed that people could develop relatedness through developing ties with others.

This helps people to overcome their separateness from others in their society and feel less alone.

Excitement and Stimulation

Fromm argued that people have an inherent need for excitement and stimulation and display a tendency to seek pleasure and be actively interested in people, things, and ideas (Fromm, 2017).

Citing Karl Bühler, Fromm believed that people find inherent pleasure in being functional (Funktionslust) and doing activities.

Effectiveness

This activity, however, does not alone satisfy human needs, in Fromm’s view. Instead, Fromm believed that people need to do creative work that meaningfully affects the world.

He believed that people have a need to affect something because this effect asserts that someone is not impotent but alive and functioning human (Fromm, 2000).

To illustrate the need for effectiveness, Fromm borrowed Marx’s example of the medieval artisan.

The artisan., Fromm believed, was a productive and original individual who enjoyed the process of work (Fromm, 2017).

The physical result of artisanship responded to the deep need not just for stimulation or activity itself but for effectiveness.

Sense of Identity

Fromm’s sense of identity is also derivative of and dependent upon the core needs for relatedness and effectance.

Fromm believed that being in a strange and overwhelming world, people can feel incompetent. To compensate for the real possibility of feeling passive — and losing one’s sense of will — people must acquire a sense of being able to do something.

This ability to be effective forms someone’s identity (Fromm, 2000).

Frame of Orientation

Another need related to a sense of identity was for a frame of orientation.

This frame of orientation takes the form, according to Fromm, of both a frame of reference and an object of devotion around which someone can organize and direct their actions.

This frame of reference can provide a coherent map of the world, providing people with an understanding of the world and their place in it (Fromm, 2017)

Transcendence

Finally, Fromm emphasized the need for transcendence.

This need for transcendence, traditionally used in theology, describes people’s tendency to transcend their self-centered and isolated position in the world to one of “being related to others, of openness to the world, escaping the hell of self-centeredness and hence self-imprisonment” (Fromm, 2000).

Fromm believed that religion could serve this need.

Analysis of Religion and its Relation to Human Development

Fromm believed that life was a struggle between three fundamental dichotomies: freedom and determinism, separateness and unity, and knowledge and ignorance.

Fromm was notable for his neo-Freudian critique of religion. He believed that religion is an escape from responsibility — and that reason is always better than religion.

While priests and psychoanalysts both deal with the soul, Fromm asserted, only the psychoanalyst makes the individual the responsible authority (Tillich, 1955).

Yet, Fromm also believed that everyone has a religious need. People, according to Fromm, need meaning in life and a deeper way of orienting to the world than reason alone can provide. Unlike Freud, Fromm believed that religion was inevitable.

As a result, Fromm sought to distinguish between good and bad religion.

He considered bad, or “authoritarian religion,” to be that where people are made inappropriately subservient to a higher power and are therefore forced to sacrifice their integrity (Tillich, 1955).

Meanwhile, what Fromm calls “humanistic religion” centers on the strength of human beings over their powerlessness and assumes that what fulfills individuals is good. The goal of humanistic religion, according to Fromm, was self-realization, not obedience to authority.

References

Das, A. K. (1993). The dialectical humanism of Erich Fromm. (2), 50-60.

Fromm, E. (1951). Märchen, Mythen, Träume. Eine Einführung in das Verständnis einer vergessenen Sprache.

Fromm, E. (1959). Psychoanalysis and Zen buddhism. Psychologia, 2(2), 79-99.

Fromm, E. (1964). Creators and destroyers. The Saturday Review, New York (4.1. 1964), pp. 22-25.

Fromm, E. (2000). The art of loving: The centennial edition. A&C Black.

Fromm, E., & Anderson, L. A. (2017). The sane society. Routledge.

Maccoby, M. (1980). Erich Fromm. Biographical Supplement of the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, New York 1980. pp. 215-220.

Tillich, P. (1955). Erich Fromm’s the sane society. Pastoral Psychology, 6(6), 13-16.